Trash and Treasure垃圾与财富

作者: 奥利弗·温赖特 刘晶晶

It’s now a hundred times more lucrative to mine gold from e-dumps than from the ground. A new show reflects on how we can reverse throwaway culture。如今,从电子垃圾堆中提取黄金的利润是从地下开采黄金的一百倍。一场展览就如何摈弃一次性文化展开思考。

How will this age be remembered? After the stone age, the bronze age, the steam age and the information age, what material or innovation will most define the current era? According to a new exhibition at London’s Design Museum, the most ubiquitous hallmark of the Anthropocene1 is not a gamechanging material, nor the mastery of technology. It’s trash.

“We are arguably living in the waste age,” says Justin McGuirk, the museum’s chief curator, who has spent three years rifling through rubbish with co-curator Gemma Curtin to put together this timely show. “The production of waste is absolutely central to our way of life, a fundamental part of how the global economy operates. We wanted to show how design is deeply complicit2 in the waste problem—and also best placed to address it.”

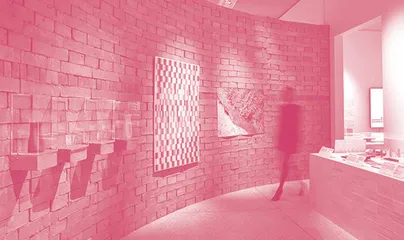

Waste Age, which opened on the eve of the Cop26 climate summit, is a wake-up call, not so much to consumers, but to the manufacturers, retailers and, most crucially, government regulators. It is not intended to be a rebuke for buying that take away coffee on your way to the museum, or forgetting your cotton tote bag, but an eye-opening look at the sheer scale of the issue, and the people working on ingenious solutions.

The exhibition begins with a useful reminder that we didn’t get here by accident. Humans are not inherently wasteful creatures. Throwaway culture was something we had to learn—indeed, it was a lifestyle choice, marketed from the mid 20th century onwards as a decadent release, following the austerity of wartime. It was the intentional opposite of “make do and mend3”. One advert from the 1960s extols the wonders of the new-fangled4 polystyrene cup: “New and very in! The party ‘glass’ you just enjoy … and throw away.” It hangs next to a plastic carrier bag from the 1980s, printed with descriptions of its many advantages over paper. Little did we know that, four decades later, the world would be consuming more than a million plastic bags a minute.

Generating waste, the curators argue, has long been a primary engine of the economy. The history of the lightbulb is an illuminating case in point. In the 1920s, bulbs were so long-lasting that they were deemed commercially unviable5. General Electric, Philips and others formed the Phoebus cartel in 1924 to standardise the life expectancy of lightbulbs at 1,000 hours—down from the previous 2,500 hours. And so the culture of planned obsolescence6 was born. Almost a century later, similar practices continue: last year Apple agreed to pay up to $500m, after it was accused of deliberately slowing down older phone models to encourage consumers to buy the latest handsets.

A striking installation by Ibrahim Mahama brings home the reality of where such defunct electronics end up. He has erected a giant wall of old TV monitors that play clips from Agbogbloshie in Ghana, for many years the world’s largest e-waste dump, where informal workers burn electrical cables to harvest the copper wire and other precious metals. Mahama has commissioned them to cast the salvaged7 metal in the form of TV screen surrounds8, which frame footage9 showing this toxic process. The scenes are desperate, but the message is clear: waste is precious.

About 7% of gold supplies are trapped inside existing electronic devices, meaning that, according to some estimates, by 2080 the largest metal reserves will not be underground but circulating inside products. What’s more, one tonne of extracted gold ore yields 3g of gold, whereas recycling one tonne of mobile phones yields 300g. So waste dumps and landfill sites are the new resource-rich mines.

“In many ways ‘waste’ is a category error,” says McGuirk. “It’s often perfectly good material that’s simply undervalued.” The exhibition includes designers who are already working on what a future of “above-ground mining” might look like, exploring how objects and buildings can be dismantled and their parts reused. There is the work of the pioneering Belgian group Rotor, a team of architects who set up a demolition company to carefully remove materials and components from buildings slated for10 the wrecking ball.

Their Brussels warehouse brims with11 everything from marble slabs to vintage lamps, the spoils of what they call “forestry in the city”. It is shown alongside the refurbishment12 projects of French architects Lacaton & Vassal, for whom demolition is “a waste of energy, a waste of material, a waste of history [and] an act of violence”. At a time when global construction waste is set to double to 2.2bn tonnes a year by 2025, their joint calls to reuse what we already have couldn’t be more urgent.

In the consumer goods sphere, the reuse cause is championed by the likes of iFixit, an online global repair platform that publishes free repair guides and sells spare parts and tools, such as a screwdriver to disassemble the iPhone. iFixit has been lobbying governments for repairability legislation since 2003, with some success.

France is the first country in Europe to implement a Repairability Index, adopted in January, which requires manufacturers to provide clear information on the repairability of smartphones, laptops, washing machines, televisions and lawnmowers, and award their products scores out of 10. The iPhone 11 may include some recycled rare-earth elements, but it got a repairability score of 4.5 out of 10.